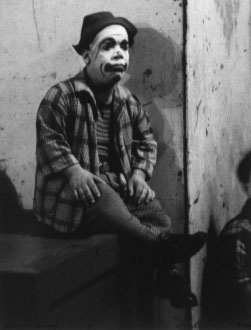

Lou Bernstein (1911 - 2005)

TRIBUTE

A Testimonial Tribute To a Mentor and Friend

from

Fred Casden

Photographer

Lou Bernstein

1911 - 2005

from

Fred Casden

Photographer

Lou Bernstein

1911 - 2005

I can’t claim to be the finest student Lou Bernstein ever had. With considerable effort, I did begin to produce images that met his standards and that I am proud of even today, but there were many others who did the same. Besides, the single most important lesson I learned from my teacher was not to be in competition with anyone except myself, and I have always taken that to heart.

Sometime in the late 1960’s (and I can’t be more specific time-wise than that), I decided to “take up” photography. In those days, I used to hang out at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC and had the opportunity to see some wonderful work on their walls by photographers like Dorothea Lange, Cartier-Bresson, and Andre Kertesz. Something struck a chord in me; “that’s the kind of endeavor I’d like to try.” Perhaps I thought that indulging my artistic spirit might help me figure out what I was supposed to do with my life. After some hesitation (and the acquisition of my first credit card), I took the subway one afternoon from MOMA on 53rd St. down to The Camera Barn on 6th Ave. and 32 St., and purchased my first camera, a Pentax Spotmatic single lens reflex for about $110.

It’s hard to remember back to a time when there were actual camera stores, places that sold nothing else except photographic supplies: cameras, lens, tripods, all kinds of darkroom equipment, chemicals, paper, and, of course, film. In those days, there were lots of photographers wandering around, many of whom belonged to camera clubs, some who were truly interested in what they saw around them and others who more enjoyed working or playing in a darkroom. So there were lots of stores that catered to this very large niche market. Fifty yards away from the Camera Barn was Olden Camera where Dick, a friend-to-be worked, and 100 yards away on 32nd St was an enormous operation, Willoughby’s, where Lou Bernstein worked, all the way in the back in the darkroom section – although I didn’t know that at the time.

Within a matter of weeks I had acquired everything I needed to get started; I was able to take photographs, develop the film, and make what I was convinced at the time were decent little prints – which I showed still dripping wet from the chemicals to anyone who happened to be around. And I continued this way for over a year – until I realized I was flying by the seat of my pants, heading for a wall of futility.

There is what I call the “photographic fallacy.” There is almost nothing easier than taking a photograph. In 2012, it’s a joke. There are all these people snapping images with cell phones, which have the temerity of making a sound like a shutter (as if anyone under a certain age has actually ever heard a real camera shutter open and close!). But even back then, when you still had to remember to put film in your camera and decide what aperture and shutter speed you wanted, it was easier than doing a lot of other things: playing the piano, preparing a good meal, solving a quadratic equation. Many people shied away from darkroom activities, but there were always photo labs to do it for you. The difficult part was to capture something of interest on that little bit of celluloid; that was the trick. And I knew somehow that I wasn’t doing that at all.

To cater to the enormous interest in the subject, there were all manner of photo magazines being published; the most widely read were Popular Photography and Modern Photography. Both of these monthly publications were geared strictly to the hobbyists, with copious reviews of the newest camera and lenses and “how-to” articles about capturing sunsets and taking nice candids of your children. Then there was Camera 35, a more sophisticated endeavor, which focused more on taking one’s craft a step further. Every month there appeared a column written by one Lou Bernstein entitled Critique (with editorial assistance, as I learned later, from Nancy Starrels) that invariably got my attention. The format may not strike you as revolutionary, although nobody else was doing anything as remotely useful. Readers sent in photographs, and Lou would offer constructive criticism as to how the image could be improved. He never got involved in the strictly technical aspects, what lens to use or how to make a better print. He limited his remarks to the content of the photograph: did the subject and the background work together, was it taken from the best angle, what kind of meaning did the picture convey, and what might have been the photographer’s intention. The column was also filled with words of wisdom about “opposites” from another person unknown to me, Eli Siegel, who I assumed was long dead, given the adulatory tone in which he was mentioned.

Back in the days, The New York Times Sunday Arts and Leisure section did not have serious articles about photography, which they ranked as a hobbyist’s pursuit along with stamp and coin collecting. They did have a column of community-type announcements, and one issue contained the information that so changed my life. Lou Bernstein, it said, would be resuming his weekly workshop (for information, call this number). I saw the notice without thinking much about it; and then a day or so later I realized, “Wait a minute, that’s the same guy who writes for Camera 35!” Once I made the connection, I immediately called the number and spoke to Nancy, who was assisting him in this endeavor.

That’s how it started – with an announcement that I just happened to see; or maybe it really was meant to be. I can remember to this day walking into the studio in a commercial building on Manhattan’s East Side (which during the day was the work space of one of Lou’s colleagues). If I had kept a diary or a journal of life’s little happenings, then I might be able to recall just who besides Lou and Nancy was there that autumn evening. But essentially what happened and what I learned remains with me to this day.

There’s no way I can talk about the workshop without beginning with the two men that Lou constantly referred to, Sid Grossman and the aforementioned Eli Siegel. I quickly discovered that Siegel was quite alive at the time, but I only recently realized something that surprised me, that Grossman, Lou’s teacher, although dead for fifteen years, was two years younger than my teacher. From everything that I remember Lou saying and what I have read from others, Grossman was not a nice guy – at least he was not polite. He would berate his students, even tearing up their prints in class to show his displeasure. But he apparently was an excellent teacher, and he got the most out of the fledgling photographers who worked with him. He was also an organizer, one of the two men most responsible for the formation of the Photo League, which in the 1930’s was the only place around that offered courses in photography.

I have no idea what kind of wild things went on at League meetings, whether anything was said or done that any normal person – not J. Edgar Hoover or Joseph McCarthy -- would consider “radical,” even though the latter effectively shut the group down in the 1950’s as being subversive. It’s true that in their earlier days, some of the group did involve themselves with “radical” stuff, like photographing labor unions and strikes; but if you look at the overwhelming body of work produced by the League, much of it would be seen today as lyrical or nostalgic of the times. You could make a case that the photographs produced under the aegis of Roosevelt’s agencies like the Farm Security Administration were a lot more critical of American society, focusing on migrant workers, chain gangs, the dust bowl, and wide-spread rural poverty, than anything that alleged communists like Grossman ever made. (In all the years I knew Lou, we never spent one second discussing politics, even who to vote for. I always assumed that he was about as liberal as the next Jewish guy in Brooklyn.)

Where the Photo League was truly revolutionary was in their development of “street photography,” focusing on urban life, especially in NYC. What that meant in practice was taking a camera into a particular neighborhood or area and working there until you understood what was going on and could record the life around you. By the time I started out with my camera, a lot of us were doing just that. It’s hard to imagine that there was a time when photographers didn’t work that way, but it’s true.

If the Photo League and Grossman gave Lou the start he needed, there was still something he felt was lacking. He sensed that there was more for him to see, and he wanted to teach others what he had learned. He needed a critical vocabulary and a way of seeing that made sense to him. There was no doubt in his mind that his work improved when he began studying Aesthetic Realism with Eli Siegel. Now one must be careful here. At its worst, this philosophy can become all-consuming and its adherents cultish and obsessive. Whether or not it was his conscious intention, Lou managed the difficult feat of integrating Siegel’s aesthetic philosophy into his approach without getting into the self-generating paranoia that gripped many of Siegel’s students. He never called himself a “Victim of the Press,” as Siegel’s follower maintained they were. Nor did he insist that his students become card-carrying members of the movement, attending classes in Siegel’s tiny studio.

Obviously, I did not know much, if anything, about Sid Grossman or Eli Siegel when I joined Lou’s workshop. I just wanted some help with my work; nothing fancy! Each student was invited to bring in some work – the more recent the better – for everyone to look at. You were encouraged to talk about your pictures: what you felt at the time and what you were trying to accomplish. Anyone else could chime in, provided you observed the ground rules. You had to be constructive; whatever you said had to be for the purpose of helping the other photographer improve his work, not to make yourself seem important. At the appropriate time, Lou would interject his own perspective. If you had imagined that your latest opus was worthy of immediate inclusion in the pantheon of great images, and Lou was calling it a “stepping stone,” (one of his favorites expressions of encouragement), you may not have been thrilled to death, but you had to accept his judgment – not because he insisted that you do so, but because you knew that he knew what he was talking about. From time to time, Lou would bring in some of his own work – not to show off that he was a master photographer and you were a novice – but because he was a participant in his workshop; we needed to talk about his work as much as we did about our own.

There were several things about Lou’s workshops that I especially remember. The first was his self-appointed role as bubbe meisse debunker. Before he began the task, he would make certain that the student understood the concept of a bubbe meisse. This kind of fanciful story didn’t need to be related by a bubbe, an old Yiddish grandmother. It was universal; anyone could spin a yarn, even those of us whose Yiddish was sadly lacking. Someone might come in with a photograph of two people sitting on a park bench, staring into space. Then the photographer in question would start explaining about how he (I don’t have to tell you that ‘he’ could be a ‘she’) came across the couple having the most animated conversation and wanted to photograph that. Of course, by the time he got his camera ready and starting shooting, the conversation was over. Nonetheless, the idea of the conversation was still in his mind, even if it wasn’t on the film. It became Lou’s responsibility to ever-so-gently explain what was really in the photograph and encourage the now-deflated photographer to try again and look more critically at what was in front of him. This situation would repeat itself time after time, so that even Lou’s advanced student could become assistant bubbe meisse debunkers – although we never got badges or uniforms.

Then there was meeting up with my teacher’s alter ego, “Louie the Barber.” Unlike his teacher, Sid Grossman, who would tear up his students’ photographs out of disgust and anger, Lou took a more useful tack. Someone would bring an 11x14 print, which they were proud of, even if it looked like a jumble to the rest of us. Lou would examine it carefully and respectfully, then walk over to the paper cutter on the counter and begin slicing away. When he was done, he would hold up the fragment that was left, which might have been 3x5. That miniaturized version, he would affirm, was what the student was really going for. Invariably, the student, stunned at first by this seeming desecration of his ‘masterpiece,’ would realize that Lou was right. Without being overly didactic, Lou was demonstrating his own principle of “inclusion and exclusion” to us by removing everything that was unessential to the image. (The reverse was also true; the subject would need some room ‘to breathe,’ more than the photographer had provided in the print.)

Sometimes, something seems so simple and self-evident that you assume you knew it all along. You are, therefore, surprised and indignant that another person would claim it as his own idea. Of course, critics and philosophers talked about “Opposites” centuries and millennia before Eli Siegel came up with Aesthetic Realism, and I can understand why proponents of this viewpoint would be upset that so many ‘non-believers’ would fail to give him credit for his theory about the centrality of opposites in art and life – although their anger and paranoia were and are beyond excessive.

Lou talked about truth and imagination, simplicity and complexity, and freedom and order in his workshop because he believed that these distinctions were important and useful in teaching. Being the kind of stubborn son-of-a-gun that I came to love, it didn’t matter one bit to him what anybody else thought. There was no way he could help a beginning photographer without confronting logic and emotion head on. The fledgling would head out, camera in hand, and find something that really excited him. He would get so caught up in the situation that he wouldn’t notice that if he moved three feet to the right he would have a much better angle; that where he was standing there was a kid’s head in the way. He might even forget to focus his lens or obtain the right exposure (yes, junior, we had to do all that in our day!). He might even forget to put film in his camera (I plead guilty). Another teacher might chide his student for that kind of rookie mistake and let it go at that, but Lou was intent on drawing a larger lesson. Once a fledgling photographer became comfortable with his equipment and began to notice what was in his viewfinder, the fun was just beginning.

When a student brought in a photograph for criticism, there was always one question that Lou would always ask – although he might have phrased it in different ways. “What was your purpose?” Even if you weren’t aware of it at the time (far from uncommon!), looking at the picture in the cold light of day, i.e., in a room full of your fellow photographers, what interested you enough to press the shutter? And then out of a roll or two of film you exposed, why did you decide to print it, and bring it in to class? What it came down to was, did you have an honest emotion about something and were you able to communicate it visually? Or were you just ladling out another bubbe meisse?

At the time when I began studying with Lou, the world of photography was expanding, filled with styles and trends radically different from the approach taken by the Photo League. Let’s just say that many photographers at that time had no use for The Family of Man way of dealing with reality, and leave it at that. A lesser man than Lou Bernstein might have joined the bandwagon, forsaking what he had spent years learning and perfecting. But the fame and fortune now coming to X or Y failed to interest him and he continued to work and teach the way he always had. In effect, Lou’s students were self-selecting; they either bought into Lou’s approach, or they went elsewhere. Some stayed for a while and then went out on their own to use what they had absorbed. Some of us kept coming back. Personally, I felt that I was better off with his on-going instruction than without it. I’m not a big believer in re-inventing the wheel. (There was something endearing about how Lou felt about his students. Once you had studied with him, then in his eyes you remained forever under his tutelage. I remember years later, Lou introducing me and several of our colleagues as “my students” – in the same way as a mother would introduce her forty year old ‘son.’ I guess you could consider that demeaning or as a badge of honor.)

What I realized early on in my studies with Lou was that becoming a serious photographer was in its own way a process – just as developing film and making prints was a chemical process – and could not be speeded up. It involved constant effort and considerable thought. You had to go out week after week and find something to photograph; sometimes you’d be on top of the world and it seemed easy, and other times, there was nothing that seemed at all appealing. You’d do your darkroom work and bring in what you had. At the beginning, what you had were ‘stepping stones” or small prints that had survived Lou’s ‘tonsorial’ efforts. After a while, you would start bringing in a few images that stood on their own – although the production was irregular and almost accidental. The one obvious pitfall that all of Lou’s students needed to avoid was over-intellectualizing, neglecting to click the shutter while you were pondering the relationship of freedom and order, or some such. The trick was to clear your mind and do your work; then when you were done and you had made your prints, to begin looking critically at what you had done. And if you weren’t as critical as you needed to be, well, there was a whole bunch of people, basically on your side, who would assist you in the process. After a while, the entirety of what you needed to know became second nature to you. You could figure out immediately that something wouldn’t ‘work,’ because everything would come out the same shade of grey; or you should wait until a better moment presented itself, and you had a good idea what that better moment might be. Then, and only then, were you able to start producing strong work reasonably consistently. Somewhere along the way, your darkroom technique would start improving too!

As I mentioned, The Photo League advocated “street photography.” You didn’t have to go to a war zone, a crime scene, a natural disaster, or some exotic locale to work. You could work in places that were familiar to you and you could get to easily. That approach certainly suited Lou’s style and his temperament. He did his work basically in his own back yard. (Though it’s not true that he never left Brooklyn; he did some of his finest work in the old Fulton Fish Market and the Bronx Zoo). One practical implication of this approach was that you could keep going back to the same area time after time. If you weren’t satisfied with what you had done – or even if you were, but you thought that you had just scratched the surface – you could keep trying and trying until you had done all that you could do. And then you would realize that there were still subtle things you hadn’t seen – for when you’re photographing people and places that are seemingly very ordinary, you had better be on the lookout for the ‘little things in life’ that are so meaningful.

Another benefit of Lou’s modus operandi was that sometime his students got to go along with him. Talk about teaching by example! I learned a lot from Lou in his workshops, but I may have learned even more working alongside of him at the P.O.N.Y Foundation, The Zoo and the Aquarium, Central and Prospect Park, the boardwalk at Coney Island, and the Canarsie Pier. Lou was always there to help his students, sharing what he had already learned about what would work and what wouldn’t. It wasn’t just that he was an amazingly generous individual. He had learned something, and if you were with him, you’d learn it also. Lou would be photographing something with four or five of his students crowding around clicking away. A week or so later, we would all bring in what we had done and compare. To this day, I remember one time when we were walking along the beach at Coney Island, and we stopped to photograph some children playing at the edge of the water. Later, when Lou showed a print he had made, I was astounded.

“I was standing next to you, but I didn’t see that!” While I had seen nothing out-of-the-ordinary (and my photographs showed it), he had seen a subtle gesture, a momentary relationship, that translated into a powerful image. My teacher understood that there could be fifty people standing next to him, but nobody, no one, would see the way he did and photograph the way he would. He was never worried about one of his students ‘stealing’ his shot. The same experience occurred to me often enough that I had to realize it wasn’t a fluke. Several of us would be out together, and we never once came back with the same images. What a liberating experience: first hand proof that nobody else can be me, and I needn’t worry about anybody trying.

After a few years, Lou’s workshop – as a commercial venture – came to an end. I don’t remember exactly what happened, but at some point we stopped going to the studio in the East 30’s. With most teachers, that would have been the end of it. So long, nice knowing you. You have to remember that Lou was not like ‘most people.’ What he did next was hold sessions in the back room of his apartment, on the second floor of a two-family house on E. 5th St. in Brooklyn. Since he had no expenses (not even subway fare!), he didn’t charge any of us. Not only was I getting the best advice and encouragement that money could buy, I wasn’t paying for it. It couldn’t have gotten any better than that.

The years passed one by one (but you knew that already); Lou wasn’t getting any younger (you knew that as well). Lou still considered himself a student of Eli Siegel, although, to my knowledge, he was no longer attending classes. He was more and more inclined to focus his camera on one small area, doing less and less walking. He spent years, several times a week, at the Aquarium at Coney Island, standing in front of the large enclosure for the beluga whales or the shark tanks, photographing seemingly the same things over and over again. On our own, most of us would have spent no more than fifteen minutes looking at the finny creatures that Lou kept working with, but he kept at it with the same zeal, I imagine, that prompted Claude Monet to reimagine his water gardens at Giverny year after year.

At some point, the Bernsteins moved from their apartment to a place all the way out on Nostrand Ave. It would be harder and harder to see Lou at all, let alone to join him at the Canarsie Pier. I kept in touch with him by phone for a number of years, but it was never the same. We needed to share photographs, and we could no longer do that. Millie had not been well for quite a while, and Lou was spending more and more of his time caring for his infirm wife. There were times when he seemed overwhelmed by his circumstances, and there was nothing I could do to be of use. Little by little, we lost touch with each other. To be honest, I had not known that they had moved to Florida until years later.

Does that mean that I forgot about my old teacher? Not in the least. I continue to have ‘conversations’ in my head with him – with alarming frequency. Usually they take the form of discussions at his workshop. Sometimes we agree. Sometimes I have to tactfully put forth a somewhat different point of view, but in a way that causes Lou to agree with me. (It’s like playing chess with yourself).

Forty or so years have passed since our first meeting. I have my own body of work, had my own exhibitions, and passed on what I have learned to a number of people. In that, I am not alone. Other students of this master photographer have had their own successes, some greater than mine. Most of them would acknowledge where their foundation came from. For myself, I put it this way, “He opened the door and turned on the light.” How many people in your life can you say that about?

Sometime in the late 1960’s (and I can’t be more specific time-wise than that), I decided to “take up” photography. In those days, I used to hang out at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC and had the opportunity to see some wonderful work on their walls by photographers like Dorothea Lange, Cartier-Bresson, and Andre Kertesz. Something struck a chord in me; “that’s the kind of endeavor I’d like to try.” Perhaps I thought that indulging my artistic spirit might help me figure out what I was supposed to do with my life. After some hesitation (and the acquisition of my first credit card), I took the subway one afternoon from MOMA on 53rd St. down to The Camera Barn on 6th Ave. and 32 St., and purchased my first camera, a Pentax Spotmatic single lens reflex for about $110.

It’s hard to remember back to a time when there were actual camera stores, places that sold nothing else except photographic supplies: cameras, lens, tripods, all kinds of darkroom equipment, chemicals, paper, and, of course, film. In those days, there were lots of photographers wandering around, many of whom belonged to camera clubs, some who were truly interested in what they saw around them and others who more enjoyed working or playing in a darkroom. So there were lots of stores that catered to this very large niche market. Fifty yards away from the Camera Barn was Olden Camera where Dick, a friend-to-be worked, and 100 yards away on 32nd St was an enormous operation, Willoughby’s, where Lou Bernstein worked, all the way in the back in the darkroom section – although I didn’t know that at the time.

Within a matter of weeks I had acquired everything I needed to get started; I was able to take photographs, develop the film, and make what I was convinced at the time were decent little prints – which I showed still dripping wet from the chemicals to anyone who happened to be around. And I continued this way for over a year – until I realized I was flying by the seat of my pants, heading for a wall of futility.

There is what I call the “photographic fallacy.” There is almost nothing easier than taking a photograph. In 2012, it’s a joke. There are all these people snapping images with cell phones, which have the temerity of making a sound like a shutter (as if anyone under a certain age has actually ever heard a real camera shutter open and close!). But even back then, when you still had to remember to put film in your camera and decide what aperture and shutter speed you wanted, it was easier than doing a lot of other things: playing the piano, preparing a good meal, solving a quadratic equation. Many people shied away from darkroom activities, but there were always photo labs to do it for you. The difficult part was to capture something of interest on that little bit of celluloid; that was the trick. And I knew somehow that I wasn’t doing that at all.

To cater to the enormous interest in the subject, there were all manner of photo magazines being published; the most widely read were Popular Photography and Modern Photography. Both of these monthly publications were geared strictly to the hobbyists, with copious reviews of the newest camera and lenses and “how-to” articles about capturing sunsets and taking nice candids of your children. Then there was Camera 35, a more sophisticated endeavor, which focused more on taking one’s craft a step further. Every month there appeared a column written by one Lou Bernstein entitled Critique (with editorial assistance, as I learned later, from Nancy Starrels) that invariably got my attention. The format may not strike you as revolutionary, although nobody else was doing anything as remotely useful. Readers sent in photographs, and Lou would offer constructive criticism as to how the image could be improved. He never got involved in the strictly technical aspects, what lens to use or how to make a better print. He limited his remarks to the content of the photograph: did the subject and the background work together, was it taken from the best angle, what kind of meaning did the picture convey, and what might have been the photographer’s intention. The column was also filled with words of wisdom about “opposites” from another person unknown to me, Eli Siegel, who I assumed was long dead, given the adulatory tone in which he was mentioned.

Back in the days, The New York Times Sunday Arts and Leisure section did not have serious articles about photography, which they ranked as a hobbyist’s pursuit along with stamp and coin collecting. They did have a column of community-type announcements, and one issue contained the information that so changed my life. Lou Bernstein, it said, would be resuming his weekly workshop (for information, call this number). I saw the notice without thinking much about it; and then a day or so later I realized, “Wait a minute, that’s the same guy who writes for Camera 35!” Once I made the connection, I immediately called the number and spoke to Nancy, who was assisting him in this endeavor.

That’s how it started – with an announcement that I just happened to see; or maybe it really was meant to be. I can remember to this day walking into the studio in a commercial building on Manhattan’s East Side (which during the day was the work space of one of Lou’s colleagues). If I had kept a diary or a journal of life’s little happenings, then I might be able to recall just who besides Lou and Nancy was there that autumn evening. But essentially what happened and what I learned remains with me to this day.

There’s no way I can talk about the workshop without beginning with the two men that Lou constantly referred to, Sid Grossman and the aforementioned Eli Siegel. I quickly discovered that Siegel was quite alive at the time, but I only recently realized something that surprised me, that Grossman, Lou’s teacher, although dead for fifteen years, was two years younger than my teacher. From everything that I remember Lou saying and what I have read from others, Grossman was not a nice guy – at least he was not polite. He would berate his students, even tearing up their prints in class to show his displeasure. But he apparently was an excellent teacher, and he got the most out of the fledgling photographers who worked with him. He was also an organizer, one of the two men most responsible for the formation of the Photo League, which in the 1930’s was the only place around that offered courses in photography.

I have no idea what kind of wild things went on at League meetings, whether anything was said or done that any normal person – not J. Edgar Hoover or Joseph McCarthy -- would consider “radical,” even though the latter effectively shut the group down in the 1950’s as being subversive. It’s true that in their earlier days, some of the group did involve themselves with “radical” stuff, like photographing labor unions and strikes; but if you look at the overwhelming body of work produced by the League, much of it would be seen today as lyrical or nostalgic of the times. You could make a case that the photographs produced under the aegis of Roosevelt’s agencies like the Farm Security Administration were a lot more critical of American society, focusing on migrant workers, chain gangs, the dust bowl, and wide-spread rural poverty, than anything that alleged communists like Grossman ever made. (In all the years I knew Lou, we never spent one second discussing politics, even who to vote for. I always assumed that he was about as liberal as the next Jewish guy in Brooklyn.)

Where the Photo League was truly revolutionary was in their development of “street photography,” focusing on urban life, especially in NYC. What that meant in practice was taking a camera into a particular neighborhood or area and working there until you understood what was going on and could record the life around you. By the time I started out with my camera, a lot of us were doing just that. It’s hard to imagine that there was a time when photographers didn’t work that way, but it’s true.

If the Photo League and Grossman gave Lou the start he needed, there was still something he felt was lacking. He sensed that there was more for him to see, and he wanted to teach others what he had learned. He needed a critical vocabulary and a way of seeing that made sense to him. There was no doubt in his mind that his work improved when he began studying Aesthetic Realism with Eli Siegel. Now one must be careful here. At its worst, this philosophy can become all-consuming and its adherents cultish and obsessive. Whether or not it was his conscious intention, Lou managed the difficult feat of integrating Siegel’s aesthetic philosophy into his approach without getting into the self-generating paranoia that gripped many of Siegel’s students. He never called himself a “Victim of the Press,” as Siegel’s follower maintained they were. Nor did he insist that his students become card-carrying members of the movement, attending classes in Siegel’s tiny studio.

Obviously, I did not know much, if anything, about Sid Grossman or Eli Siegel when I joined Lou’s workshop. I just wanted some help with my work; nothing fancy! Each student was invited to bring in some work – the more recent the better – for everyone to look at. You were encouraged to talk about your pictures: what you felt at the time and what you were trying to accomplish. Anyone else could chime in, provided you observed the ground rules. You had to be constructive; whatever you said had to be for the purpose of helping the other photographer improve his work, not to make yourself seem important. At the appropriate time, Lou would interject his own perspective. If you had imagined that your latest opus was worthy of immediate inclusion in the pantheon of great images, and Lou was calling it a “stepping stone,” (one of his favorites expressions of encouragement), you may not have been thrilled to death, but you had to accept his judgment – not because he insisted that you do so, but because you knew that he knew what he was talking about. From time to time, Lou would bring in some of his own work – not to show off that he was a master photographer and you were a novice – but because he was a participant in his workshop; we needed to talk about his work as much as we did about our own.

There were several things about Lou’s workshops that I especially remember. The first was his self-appointed role as bubbe meisse debunker. Before he began the task, he would make certain that the student understood the concept of a bubbe meisse. This kind of fanciful story didn’t need to be related by a bubbe, an old Yiddish grandmother. It was universal; anyone could spin a yarn, even those of us whose Yiddish was sadly lacking. Someone might come in with a photograph of two people sitting on a park bench, staring into space. Then the photographer in question would start explaining about how he (I don’t have to tell you that ‘he’ could be a ‘she’) came across the couple having the most animated conversation and wanted to photograph that. Of course, by the time he got his camera ready and starting shooting, the conversation was over. Nonetheless, the idea of the conversation was still in his mind, even if it wasn’t on the film. It became Lou’s responsibility to ever-so-gently explain what was really in the photograph and encourage the now-deflated photographer to try again and look more critically at what was in front of him. This situation would repeat itself time after time, so that even Lou’s advanced student could become assistant bubbe meisse debunkers – although we never got badges or uniforms.

Then there was meeting up with my teacher’s alter ego, “Louie the Barber.” Unlike his teacher, Sid Grossman, who would tear up his students’ photographs out of disgust and anger, Lou took a more useful tack. Someone would bring an 11x14 print, which they were proud of, even if it looked like a jumble to the rest of us. Lou would examine it carefully and respectfully, then walk over to the paper cutter on the counter and begin slicing away. When he was done, he would hold up the fragment that was left, which might have been 3x5. That miniaturized version, he would affirm, was what the student was really going for. Invariably, the student, stunned at first by this seeming desecration of his ‘masterpiece,’ would realize that Lou was right. Without being overly didactic, Lou was demonstrating his own principle of “inclusion and exclusion” to us by removing everything that was unessential to the image. (The reverse was also true; the subject would need some room ‘to breathe,’ more than the photographer had provided in the print.)

Sometimes, something seems so simple and self-evident that you assume you knew it all along. You are, therefore, surprised and indignant that another person would claim it as his own idea. Of course, critics and philosophers talked about “Opposites” centuries and millennia before Eli Siegel came up with Aesthetic Realism, and I can understand why proponents of this viewpoint would be upset that so many ‘non-believers’ would fail to give him credit for his theory about the centrality of opposites in art and life – although their anger and paranoia were and are beyond excessive.

Lou talked about truth and imagination, simplicity and complexity, and freedom and order in his workshop because he believed that these distinctions were important and useful in teaching. Being the kind of stubborn son-of-a-gun that I came to love, it didn’t matter one bit to him what anybody else thought. There was no way he could help a beginning photographer without confronting logic and emotion head on. The fledgling would head out, camera in hand, and find something that really excited him. He would get so caught up in the situation that he wouldn’t notice that if he moved three feet to the right he would have a much better angle; that where he was standing there was a kid’s head in the way. He might even forget to focus his lens or obtain the right exposure (yes, junior, we had to do all that in our day!). He might even forget to put film in his camera (I plead guilty). Another teacher might chide his student for that kind of rookie mistake and let it go at that, but Lou was intent on drawing a larger lesson. Once a fledgling photographer became comfortable with his equipment and began to notice what was in his viewfinder, the fun was just beginning.

When a student brought in a photograph for criticism, there was always one question that Lou would always ask – although he might have phrased it in different ways. “What was your purpose?” Even if you weren’t aware of it at the time (far from uncommon!), looking at the picture in the cold light of day, i.e., in a room full of your fellow photographers, what interested you enough to press the shutter? And then out of a roll or two of film you exposed, why did you decide to print it, and bring it in to class? What it came down to was, did you have an honest emotion about something and were you able to communicate it visually? Or were you just ladling out another bubbe meisse?

At the time when I began studying with Lou, the world of photography was expanding, filled with styles and trends radically different from the approach taken by the Photo League. Let’s just say that many photographers at that time had no use for The Family of Man way of dealing with reality, and leave it at that. A lesser man than Lou Bernstein might have joined the bandwagon, forsaking what he had spent years learning and perfecting. But the fame and fortune now coming to X or Y failed to interest him and he continued to work and teach the way he always had. In effect, Lou’s students were self-selecting; they either bought into Lou’s approach, or they went elsewhere. Some stayed for a while and then went out on their own to use what they had absorbed. Some of us kept coming back. Personally, I felt that I was better off with his on-going instruction than without it. I’m not a big believer in re-inventing the wheel. (There was something endearing about how Lou felt about his students. Once you had studied with him, then in his eyes you remained forever under his tutelage. I remember years later, Lou introducing me and several of our colleagues as “my students” – in the same way as a mother would introduce her forty year old ‘son.’ I guess you could consider that demeaning or as a badge of honor.)

What I realized early on in my studies with Lou was that becoming a serious photographer was in its own way a process – just as developing film and making prints was a chemical process – and could not be speeded up. It involved constant effort and considerable thought. You had to go out week after week and find something to photograph; sometimes you’d be on top of the world and it seemed easy, and other times, there was nothing that seemed at all appealing. You’d do your darkroom work and bring in what you had. At the beginning, what you had were ‘stepping stones” or small prints that had survived Lou’s ‘tonsorial’ efforts. After a while, you would start bringing in a few images that stood on their own – although the production was irregular and almost accidental. The one obvious pitfall that all of Lou’s students needed to avoid was over-intellectualizing, neglecting to click the shutter while you were pondering the relationship of freedom and order, or some such. The trick was to clear your mind and do your work; then when you were done and you had made your prints, to begin looking critically at what you had done. And if you weren’t as critical as you needed to be, well, there was a whole bunch of people, basically on your side, who would assist you in the process. After a while, the entirety of what you needed to know became second nature to you. You could figure out immediately that something wouldn’t ‘work,’ because everything would come out the same shade of grey; or you should wait until a better moment presented itself, and you had a good idea what that better moment might be. Then, and only then, were you able to start producing strong work reasonably consistently. Somewhere along the way, your darkroom technique would start improving too!

As I mentioned, The Photo League advocated “street photography.” You didn’t have to go to a war zone, a crime scene, a natural disaster, or some exotic locale to work. You could work in places that were familiar to you and you could get to easily. That approach certainly suited Lou’s style and his temperament. He did his work basically in his own back yard. (Though it’s not true that he never left Brooklyn; he did some of his finest work in the old Fulton Fish Market and the Bronx Zoo). One practical implication of this approach was that you could keep going back to the same area time after time. If you weren’t satisfied with what you had done – or even if you were, but you thought that you had just scratched the surface – you could keep trying and trying until you had done all that you could do. And then you would realize that there were still subtle things you hadn’t seen – for when you’re photographing people and places that are seemingly very ordinary, you had better be on the lookout for the ‘little things in life’ that are so meaningful.

Another benefit of Lou’s modus operandi was that sometime his students got to go along with him. Talk about teaching by example! I learned a lot from Lou in his workshops, but I may have learned even more working alongside of him at the P.O.N.Y Foundation, The Zoo and the Aquarium, Central and Prospect Park, the boardwalk at Coney Island, and the Canarsie Pier. Lou was always there to help his students, sharing what he had already learned about what would work and what wouldn’t. It wasn’t just that he was an amazingly generous individual. He had learned something, and if you were with him, you’d learn it also. Lou would be photographing something with four or five of his students crowding around clicking away. A week or so later, we would all bring in what we had done and compare. To this day, I remember one time when we were walking along the beach at Coney Island, and we stopped to photograph some children playing at the edge of the water. Later, when Lou showed a print he had made, I was astounded.

“I was standing next to you, but I didn’t see that!” While I had seen nothing out-of-the-ordinary (and my photographs showed it), he had seen a subtle gesture, a momentary relationship, that translated into a powerful image. My teacher understood that there could be fifty people standing next to him, but nobody, no one, would see the way he did and photograph the way he would. He was never worried about one of his students ‘stealing’ his shot. The same experience occurred to me often enough that I had to realize it wasn’t a fluke. Several of us would be out together, and we never once came back with the same images. What a liberating experience: first hand proof that nobody else can be me, and I needn’t worry about anybody trying.

After a few years, Lou’s workshop – as a commercial venture – came to an end. I don’t remember exactly what happened, but at some point we stopped going to the studio in the East 30’s. With most teachers, that would have been the end of it. So long, nice knowing you. You have to remember that Lou was not like ‘most people.’ What he did next was hold sessions in the back room of his apartment, on the second floor of a two-family house on E. 5th St. in Brooklyn. Since he had no expenses (not even subway fare!), he didn’t charge any of us. Not only was I getting the best advice and encouragement that money could buy, I wasn’t paying for it. It couldn’t have gotten any better than that.

The years passed one by one (but you knew that already); Lou wasn’t getting any younger (you knew that as well). Lou still considered himself a student of Eli Siegel, although, to my knowledge, he was no longer attending classes. He was more and more inclined to focus his camera on one small area, doing less and less walking. He spent years, several times a week, at the Aquarium at Coney Island, standing in front of the large enclosure for the beluga whales or the shark tanks, photographing seemingly the same things over and over again. On our own, most of us would have spent no more than fifteen minutes looking at the finny creatures that Lou kept working with, but he kept at it with the same zeal, I imagine, that prompted Claude Monet to reimagine his water gardens at Giverny year after year.

At some point, the Bernsteins moved from their apartment to a place all the way out on Nostrand Ave. It would be harder and harder to see Lou at all, let alone to join him at the Canarsie Pier. I kept in touch with him by phone for a number of years, but it was never the same. We needed to share photographs, and we could no longer do that. Millie had not been well for quite a while, and Lou was spending more and more of his time caring for his infirm wife. There were times when he seemed overwhelmed by his circumstances, and there was nothing I could do to be of use. Little by little, we lost touch with each other. To be honest, I had not known that they had moved to Florida until years later.

Does that mean that I forgot about my old teacher? Not in the least. I continue to have ‘conversations’ in my head with him – with alarming frequency. Usually they take the form of discussions at his workshop. Sometimes we agree. Sometimes I have to tactfully put forth a somewhat different point of view, but in a way that causes Lou to agree with me. (It’s like playing chess with yourself).

Forty or so years have passed since our first meeting. I have my own body of work, had my own exhibitions, and passed on what I have learned to a number of people. In that, I am not alone. Other students of this master photographer have had their own successes, some greater than mine. Most of them would acknowledge where their foundation came from. For myself, I put it this way, “He opened the door and turned on the light.” How many people in your life can you say that about?